The June 29, 2016, "Off the Rails" INDY Week piece by David Hudnall, which discusses the Durham-Orange light rail transit project (DOLRT) is a poorly researched opinion piece that does a tremendous disservice to INDY Week readers, residents of Durham and Chapel Hill, and—most importantly—current public transit riders in Durham and Orange counties who stand to benefit greatly from a significantly enhanced bus and rail transit network with DOLRT at its core.

Hudnall’s piece mistakes anecdotes for data, ignores significant differences between Wake County and Durham-Chapel Hill, ignores the ways in which current low-income residents travel today—and what that tells us about the usefulness of DOLRT—and, finally, skips reasonable fact-checking of anti-rail project critics’ claims with publicly available documents, including past INDY Week stories on DOLRT.

In an effort to correct many of the misrepresentations of facts, and errors made by Hudnall, below are excerpts from his piece with added context, data, and information so that readers can get an accurate understanding of DOLRT, the benefits it will provide for our community, and why light rail will meet the needs of Durham and Orange Counties and move us forward.

Hudnall:

To get to work under the envisioned D-O LRT plan, however, Wells would have to take a thirty-minute ride on the Roxboro Street bus to the Dillard Street station. She'd then wait for the light-rail train to arrive, take it approximately forty minutes to Chapel Hill, then walk five minutes to the Wilson Library.

Her commute time would nearly triple, from a half hour behind the wheel to an hour and fifteen minutes on public transportation—assuming her arrivals at the bus stop and the train station are well timed. And so she says she's unlikely to wake up at 5 a.m. just so she can take the train to work. Neither would most people.

Hudnall is eager in his article to criticize the light rail for not doing enough to help low-income residents, yet he continually uses inappropriate metrics to evaluate how the light rail performs. Those who depend most on transit either do not own a car or live in a household with fewer cars that full-time workers. Rather than comparing the DOLRT line to a car trip, the correct metric is to compare a trip on DOLRT to a trip on today’s current bus network. For Ms. Wells, the current bus network shows a trip of 1 hour and 20 minutes to 1 hour and 28 minutes, giving light rail (Hudnall cites 1 hour and 15 minutes) a time savings of 5 to 13 minutes each way over the current bus service for this trip. (View this trip to Wilson Library on Google Maps.)

And before you navigate away from Google Maps, plan a trip by transit from the Holton Center in East Durham to Home Depot in Patterson Place. You’ll see it is 1 hour and 5 minutes to 1 hour and 11 minutes, with a transfer from one bus to another at Durham Station. Now consider swapping the 42-minute bus trip from Downtown Durham Multimodal Center to the Home Depot in Patterson Place for a 21-minute trip on light rail, both with a 2-3 minute walk to work at the end of the trip. This trip has been shortened to 44 to 50 minutes, a significant time savings over our current transit infrastructure.

Specifically, light rail saves this passenger 21 minutes each way. What does a shorter commute do for someone? Harvard University says it does more than virtually anything else to help someone escape poverty. The New York Times wrote in 2015:

In a large, continuing study of upward mobility based at Harvard, commuting time has emerged as the single strongest factor in the odds of escaping poverty. The longer an average commute in a given county, the worse the chances of low-income families there moving up the ladder.

The relationship between transportation and social mobility is stronger than that between mobility and several other factors, like crime, elementary-school test scores or the percentage of two-parent families in a community, said Nathaniel Hendren, a Harvard economist and one of the researchers on the study.

Hudnall:

The trip into Chapel Hill will be considerably breezier, though, for a future resident of One City Center, the giant hole in the ground in the center of downtown Durham, soon to be a twenty-seven-story mixed-use condo building. For that privileged urban denizen, it's just a two-block walk to Durham Station. Likewise, Duke students will have their pick of three on-campus stops to get them to and from a Bulls game or a show at Cat's Cradle. The Ninth Street stop on the D-O LRT is exploding with nearby apartment options—if you can spend $1,500 a month for a one-bedroom.

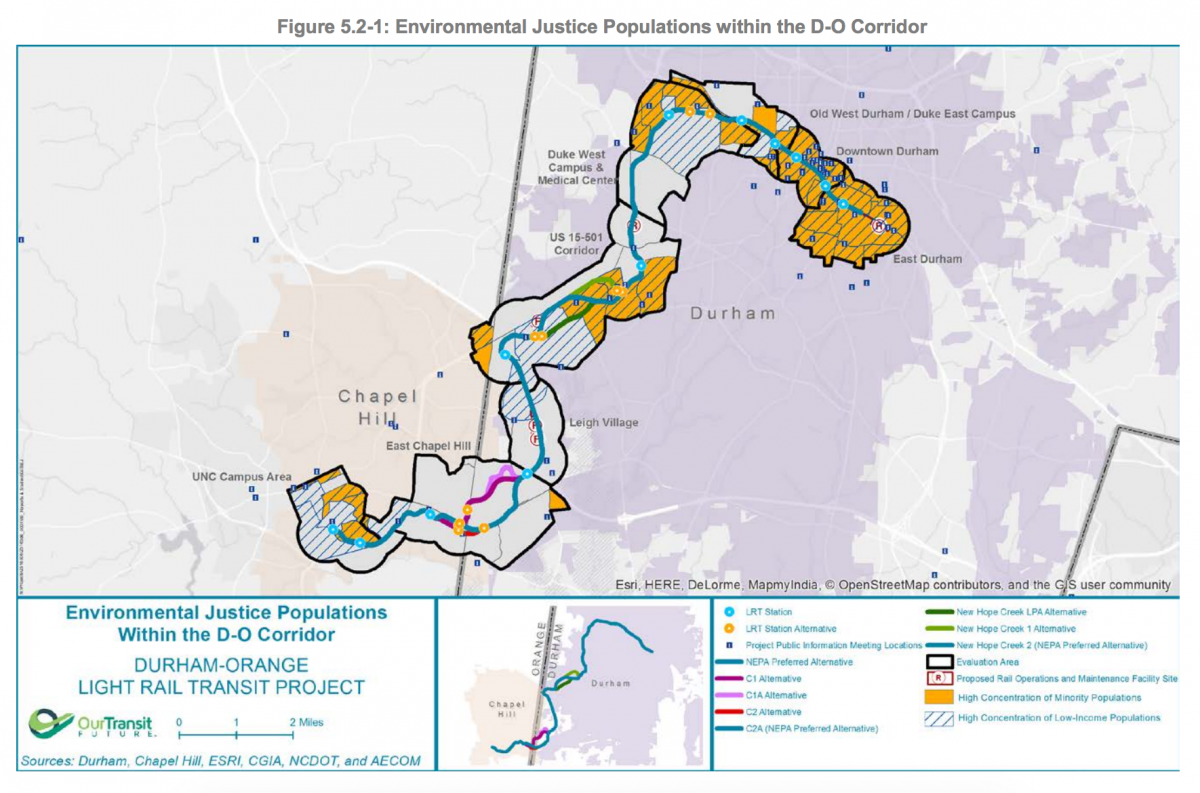

With these sentences, Hudnall—who, according to LinkedIn, arrived in Durham a mere seven months ago in December 2015—reveals that he knows very little about where low-income residents live in Durham. Under federal law, GoTriangle was required to document the concentration of low-income and minority populations along the DOLRT corridor. You can see the data and a map on pages 8-9 of chapter 5 of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement.

Here’s the map:

The blue cross-hatched areas show high concentrations of low-income residents. Yellow areas show high concentrations of minority residents. While Hudnall focuses on new buildings with high rents, he completely ignores the substantial numbers of low-income residents living in existing buildings in most of the corridor. Both Durham and Orange counties have approximately 25% of their population considered low-income, but the DOLRT corridor is 43% low-income. Hudnall misses public housing developments like the Damar Court and Morrenne Rd communities, just across Erwin Rd from the Duke campus and within walking distance of the LaSalle St rail station. He misses the census block groups near the MLK Blvd and Shannon Rd light rail stations where the Durham Neighborhood Compass reports a median income of $31,037 compared to the county average of over $52,000.

Hudnall:

...UNC and Duke, whose students are less likely to rely on public transportation…

This statement is inaccurate. Both the Duke and UNC student bodies are very heavy users of public transportation. The Duke Transit system has roughly 16,000 boardings per day. That’s why they have extra-long buses like this:

And experience lines to board like this on East Campus:

To put that ridership in perspective, Duke Transit carries more passengers on most weekdays than the City of Asheville system (population, ~83,000 people), the City of Winston-Salem Transit Authority (population, ~240,000), and roughly the same amount of passengers as the City of Greensboro (population, ~280,000).

Chapel Hill Transit, with the second-largest number of transit boardings in North Carolina after the Charlotte bus and rail system, conducted a ridership survey earlier this year and found that 55% of their 25,000-plus daily boardings were made by students (p.54).

Hudnall:

Durham County passed a half-cent sales tax for this purpose in 2011, and Orange County followed suit in 2012. But the then-Republican-heavy Wake County Board of Commissioners refused to take action. Durham and Orange pressed forward, collaborating on what is now the D-O LRT. Both counties continue to collect taxes for the project.

This statement by Hudnall completely omits the fact that the referenda in both counties funded much more than the DOLRT line, and that significant bus service improvements have already been delivered in and between both counties. Improvements made so far on GoDurham, GoTriangle, Chapel Hill Transit, and Orange Public Transit are detailed here on a GoTriangle website.

Additional improvements are coming in August. GoDurham will extend service later on Sunday evenings. GoTriangle will extend regional service to Carrboro for the first time and double the number of trips per hour in the middle of the weekday between Durham and Chapel Hill.

The INDY Week covered these improvements recently in an article written by (you guessed it) David Hudnall.

Additionally, planning for an Amtrak Station in Hillsborough is also underway as part of the Orange County plan.

Hudnall:

Nowadays, Ford articulates his gripes about D-O LRT in the context of social justice. "It takes people from one prosperous node—UNC, in Chapel Hill—to another, Duke, to another, downtown Durham," Ford says. "There won't be any real affordable housing on that line, no matter how much local governments try to make that happen. We're putting all this money into a pet project for an elite group of people."

Just like Hudnall, Dick Ford is not aware that there are low-income residents in places along the DOLRT line other than the Dillard St and Alston Avenue areas.

Hudnall:

"The ridership projections for the Durham-Orange LRT stretch credulity, with estimated daily boardings of 23,000. This is in contrast to the Charlotte LRT system, with daily boardings of 16,000—which has been static since inception in 2007, while the population has increased 17 percent…”

It is possible that David Hardman, who wrote this quote that Hudnall cites, does not know the current Charlotte line is shorter than the DOLRT line will be. The existing Charlotte line is about 9 miles long and has 16,000 boardings per day. DOLRT will be 17 miles long and have 23,000 boardings. Longer lines tend to have more passengers. The Charlotte line is currently being extended because of its success, and a new section to UNC-Charlotte will open in 2017.

Hudnall:

“...These ridership projections are further inflated with the working assumption that 40 percent of households in the Durham-Chapel Hill corridor will not own automobiles in 2040, which flies in the face of current ownership levels and assumes a tectonic shift in public behavior."

This is another quote from Hardman, and is also another example of failed fact-checking on Hudnall’s part. This talking point is a repeat of a misreading of the official DEIS documents by Alex Cabanes, seen here in a Facebook comment on September 29, 2015, made in the comments section of a News & Observer article.

Fortunately, Jeffrey Billman debunked this claim in a previous INDY Week article, stating

“For example, they have claimed that GoTriangle is assuming 40 percent of area residents will be carless by 2035. Not so, he says. Instead, the agency estimates that 40 percent of light-rail riders will be carless, which makes more sense.”

Unfortunately, Hudnall did not take the time to check his own paper’s reporting on this controversy. It’s this type of basic error that should cause all readers to ask “what else did Hudnall miss?”

Hudnall:

A Charlotte Observer story from earlier this month noted that Uber is likely contributing to declining ridership in Charlotte. Judith Mellyn, a Downing Creek attorney who grew up using public transportation in New York and voted for the half-cent tax back in 2011, says her son, who lives in Charlotte, used to take light rail to events in the city. Now he uses Uber.

"And I think that will obviously evolve into things like driverless vehicles, driverless buses—a way of getting around in the future that won't be tied to these fixed stations," Mellyn says.

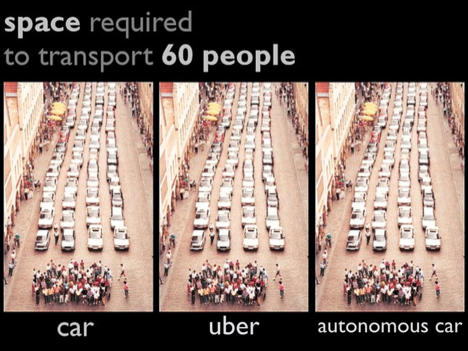

Here is an answer to this comment in pictures:

And:

The point of these photos is to show that access to dense job centers is first and foremost about fitting a lot of people into limited amounts of valuable urban space. High-capacity vehicles get the job done, carrying many people to work without taking up nearly as much space as those people would in cars. Having most people arrive at places like UNC Hospitals and Duke University Medical Center in cars carrying just one or two people is fundamentally a physics problem: You can’t fit all the people in if they all bring 2600 pounds of metal around them. Buses overcome this problem to a certain point. Trains will enable us to overcome this problem for generations to come.

Hudnall:

“...And none of the groups who looked into this came back and said light rail was the right investment for Wake County."

Gardiner continues: "We went into the process from a vulnerable position. If the community would have come back and said, 'We want light rail,' that would have been fine with us. But they didn't. They looked at the facts and said, 'We can't get the mileage and geography and service we need out of our public transportation system if we spend our money on a light-rail line. There's no flexibility. It's a big, growing, sprawling county. And with buses and BRT we can get service out to these places that need it. We would be giving up service goals in exchange for a toy we can feel good about.'"

Hudnall portrays the comments of a Wake County employee talking about decisionmaking in Wake County as having implications for Orange and Durham counties. The communities, and their transit systems, are quite different.

While it is exciting that Wake County finally has a transit plan, it is also worth noting how Wake County’s transit system is very, very far behind the system that exists in Durham and Orange counties (which is another great reason for the Wake plan- to catch up!). FiveThirtyEight did a comparison of how 290 American cities compared by transit usage, dividing trips on area transit systems by annual population to calculate trips per person per year. With 43.4 trips per person, Durham-Chapel Hill placed a very respectable 21st, just ahead of both Denver and Salt Lake City—both of which are much bigger cities with multi-line rail networks. Raleigh, on the other hand, came in 195th, narrowly beating out Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and Scranton, Pennsylvania, with 7.2 trips per person.

Orange County has a rural buffer, and Durham has limits on where it will extend water/sewer service. Wake County has comparatively few limits. For a county like Wake, which is not focusing land use planning in urban districts and continues to build new highways like the I-540 toll road, a system that can spread out with less frequent service over more land makes more sense. The same is simply not true for Orange and Durham counties.

In closing, a lot of the mistakes in this article could be chocked up to a new guy in town not doing his homework. But for a paper that proclaims to fight for social justice, and given that most people riding transit today in Durham and Chapel Hill have incomes well below the median income, (slide 10) INDY Week needs to take a harder look in the mirror and ask itself why it couldn’t be bothered to talk to low-income residents or people of color who ride transit in Durham and Chapel Hill about how they travel instead of letting several older, wealthier white residents with a clear agenda speak for them.

Given that the Herald-Sun faced appropriately stiff criticism from Bull City Rising for doing the exact same thing less than a year ago, INDY Week should have done better than this.

Thank you to Bull City Rising for cross-posting this article.

Issues:

Comments

Light Rail

Good article. A few things people don't think about enough:

1. TIME SAVED People who use mass transit, buses, rail, by virtue of not driving, can do something else, like read the news, while being in transit, so time spent on the bus is not time thrown away like when driving a car. In this way, comparing transit time in a car, and transit time on a bus or train, is comparing apples to oranges.

2. GREENSPACE SAVED The virtue of light rail is the ability to scale up and down, with demand, which means roads don't have to be over-built to meet peak use, during rush hours. This area is still growing, but we don't want to built all of these lanes that become useless pavement at all hours when there isn't peak traffic. This means roads with fewer lanes, so less pavement for our serious stormwater run-off problems. The train cars are carrying the rush hour patrons. This means, instead of having to add lanes onto Durham freeway and 15-501, the rail is carrying a higher volume of commuters in the equivalent of one lane..

3. USABLE SPACE SAVED People who use mass transit, buses and light rail don't require parking spaces in higher density areas. This means valuable urban space is not spent on parking facilities. Imagine if everyone took light rail between high density areas, you step off the train and walk to lots of shops and restaurants that used to be devoted to storing personal vehicles. Every car takes up, at least, one apartment's worth of space and lane in parking facilities, storing 2 cars may displace a small shop, 6 cars, a restaurant.... In suburban areas with asphalt parking lots, each car requires several parking spaces, as you have to hop into the car and park elsewhere for each destination you go to on your errand list. This adds up to a lot of wasted pavement and massive amounts of rapid run-off stormwater.

Hoping for more greenspace, more human activity space, and less car space,

Thanks, Jason for your comprehensive sharing.

Sarah